Covid-19 brought the concept of OneHealth to the fore and we all now know how much our health is linked to the health status of wild animals. A rapid response to emerging diseases can be the key to success. Rapid local identification of signs of changes in wildlife is therefore necessary. Only we hunters can notice these almost imperceptible signs. We are the eyes of the beholder, the hands of the toucher, we are the sentinels of global health.

In collaboration with Dr. Mario Chiari "Path-Finders" is born, an interactive column in which we will talk about infectious diseases, parasitic diseases and biological aspects of wildlife that directly affect the hunting world.

Mario, thanks to his experience in the field, will help us to understand more deeply some of the fundamental principles for a correct sanitary management of wildlife.

PERUKE ANTLERS

AFFECTED SPECIES: All cervids, but more frequently visible on roe deer.

WHAT CAN I SEE: Alterations in trophy growth. Lack of testosterone production (testicular lesions or disease) leads to a continuous trophy growth. The velvet developes irregularly forming a voluminous mass that is not followed by ossification and cleaning. The "wig" grows, increasing in volume downwards (helmet-like) or upwards (tower-like).

IS IT A ZOONOSIS? No, these are alterations of the trophy development due to hormonal imbalances (lack of testosterone production).

IS THERE A RISK TO EATING MEAT? No.

SHOULD I CONTACT THE HEALTH AUTHORITIES? Report what you have observed. Affected animals die in 3-4 years due to excessive trophy development.

MANAGEMENT INDICATIONS: Alteration caused by testicular lesions (disease or trauma) and not by management practices.

SARCOPTIC MANGE

PATHOGENIC AGENT: Sarcoptes scabiei

AFFECTED SPECIES: Mites specific to all mammals - S. Scabiei causes severe disease in ibexes and chamois of all ages.

WHAT I CAN SEE: Initially, appearance of scaly and then crusty formations on the head, neck, abdomen and legs. The strong itching due to the immune response to the mites (allergic dermatitis) forces the animal to continuous rubbing (rocks, trees) which leads to the appearance of auto-traumatic lesions (excoriations and sores) and secondary infections.

Subsequently the animal becomes progressively weaker until it dies (2-4 months).

IS IT A ZOONOSIS?: Yes, transmission of the mite by direct contact with infested animals. Use personal protective equipment for handling.

IS IT A RISK FOR MEAT CONSUMPTION? No. Although handling even slightly affected animals can be risky.

SHOULD I CONTACT THE HEALTH AUTHORITIES? Report what has been observed.

MANAGEMENT INDICATIONS: Disease not manageable in wild populations. Humane and exclusive culling of severely affected individuals.

Spotty expansion in affected populations is influenced by the density of susceptible individuals. In a free population, the occurrence of the disease leads to high mortality (70-95% of the population). Subsequently, the parasite persists, resulting in lower mortality (15-20%).

The progression is characterised by a seasonal distribution, with a minimum in autumn followed by a peak in winter-spring and a minor summer tail.

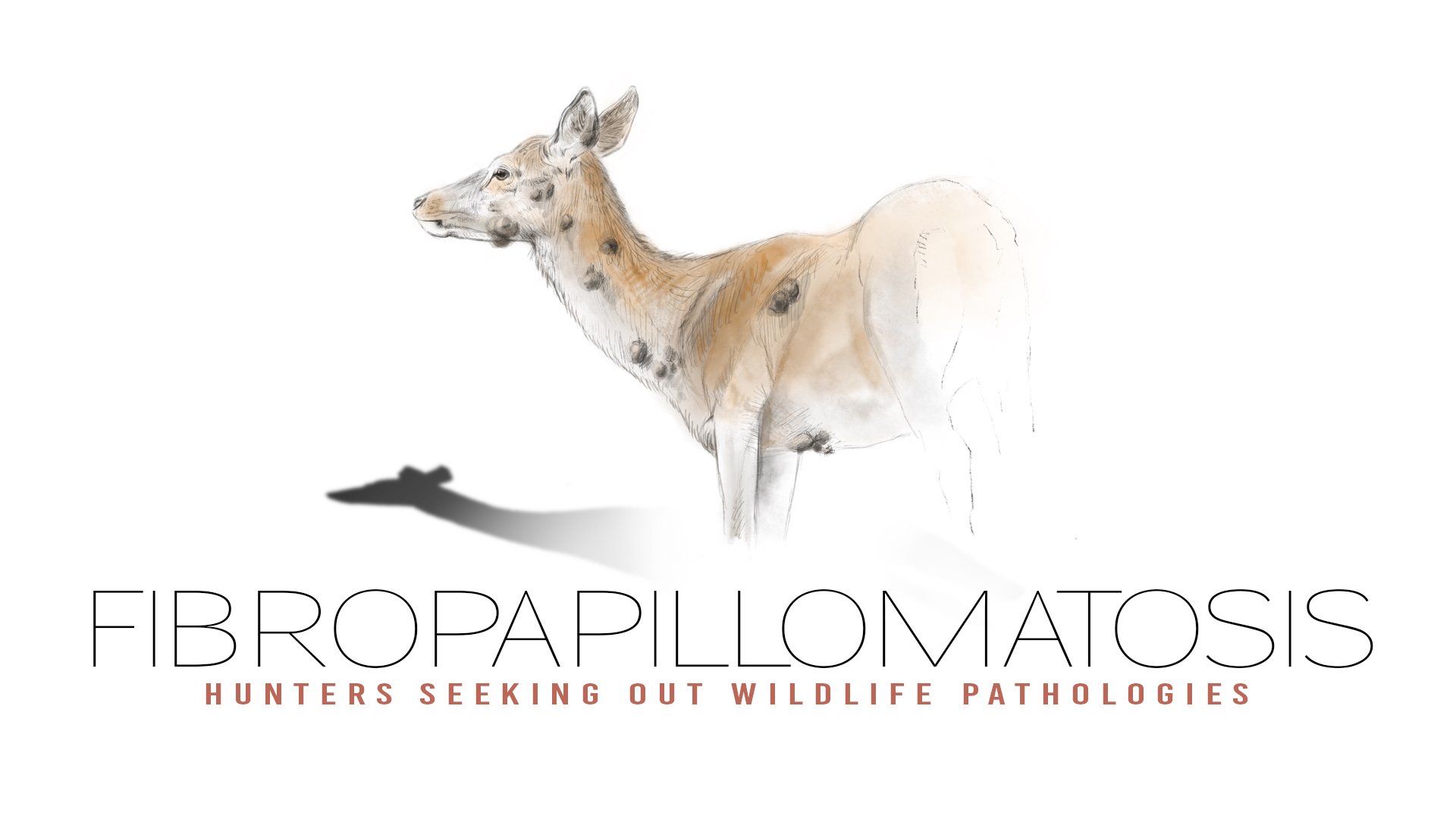

FIBROPAPILLOMATOSIS

PATHOGEN: Virus-Papovavirus

AFFECTED SPECIES: Various wild species, especially cervids (red deer, white-tailed deer, elk, roe deer, etc).

WHAT CAN I SEE: Skin tumours which appear as fibrous and painful neoformations of varying size and spread on the animal’s skin.

IS IT A ZOONOSIS?: No.

IS IT A RISK FOR MEAT CONSUMPTION?: No, although animals with chronic or widespread lesions should not be consumed.

SHOULD I CONTACT THE HEALTH AUTHORITIES?: Report the observations. If requested, take skin sample a from injured areas.

MANAGEMENT INDICATIONS: There are no specific indications. Culling animals with widespread lesions can be considered a charitable act.

AFRICAN SWINE FEVER

PATHOGENIC AGENT: Virus-Asfivirus.

AFFECTED SPECIES: Wild and domestic Suidae.

WHAT I CAN SEE: Dead wild boar in the wild, sometimes with blood coming out of the mouth. This is a primary sign of alarm. Diffuse hemorrhages and splenomegaly may be detected.

IS IT A ZOONOSIS?: No.

IS IT A RISK FOR MEAT CONSUMPTION?: Not for humans. Handling of hunted and infected animals can make humans a passive carrier of the virus causing disease in others.

SHOULD I CONTACT THE HEALTH AUTHORITIES?: Immediately report the discovery of carcasses of animals found dead or of shot animals showing lesions such as splenomegaly, diffuse hemorrhages (not from a gunshot).

MANAGEMENT INDICATIONS: These can be very different depending on the size of the infected area, but to summarise:

- Infected area: prohibit any action that could set wild boar in motion. Search for and recover all carcasses

- Area adjacent to the infected area: the eradication of the wild boar in a coordinated manner managed by police/health authorities

- Area outside infected area: drastic reduction of wild boar density through hunting activities

In all areas search for wild boar carcasses for removal because the virus remains active in the carcasses of dead animals for weeks/months.

The spread of the virus occurs through direct contact (infected/healthy animal) and through the consumption by healthy animals of meat from animals slaughtered during the viraemic phase.

ASF TRANSMISSION ROUTES

How does ASF reach a disease-free territory?

Through humans:

- Human activities that can carry the virus out of an infected area, such as abandoning food (waste) produced from infected animals that had no ASF symptoms (early days of infection).

- Areas at risk: impossible to predict

- Risk very difficult to mitigate and impossible to predict

Through wild boar:

- Contact between a healthy boar and an infected boar (also carcass).

- Risk areas: areas adjacent to infected areas. The virus moves 1 km per week/month depending on the density of wild boar.

- Easy to predict but difficult to prevent

ASCARIDIOSIS or MILK SPOT LIVER

PATHOGEN: Parasite-Ascaris suum.

AFFECTED SPECIES: Wild boar and Pig.

WHAT CAN I SEE: Parasitic hepatitis with white spots and parasitic pathways in the liver of wild boar given by the migration of worm larvae. Long white worms(40cm) in the intestine.

IS IT A ZOONOSIS? Occasional, but very rare due to wild boar.

IS IT A RISK TO MEAT CONSUMPTION? No, if meat is handled properly and with hygienic care (avoid contamination with boar faeces during processing).

SHOULD I CONTACT THE HEALTH AUTHORITIES? No, it is a widespread disease.

MANAGEMENT INDICATIONS: Parasite frequency is related to wild boar density. Possible management depends on this factor.